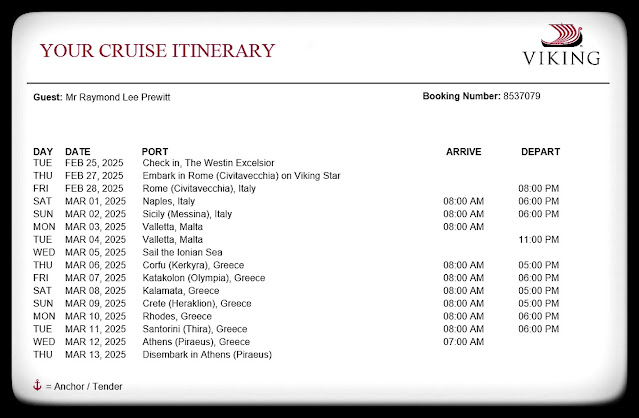

We left Sacramento by air around 8AM Pacific Time on Monday the 24th of February and landed in Rome the next morning around 8:30 Central European Time.

As part of our cruise package we began our trip to Rome with a few days in the Westin Excelsior Hotel. We were so tired when we arrived Tuesday morning, we slept nearly all day.

Ready or not, Wednesday was our first full vertical day in Rome. By the end of the day, however, I was exhausted again. I was so exhausted I would begin a sentence saying something coherently, and before the end of the sentence I would literally be speaking jibberish.

Rome

|

| Piazza della Republica |

The first building we explored was the Basilica of St. Mary of the Angels and Martyrs, across from the Piazza della Republica and near the National Museum of Rome.

I was so impressed I almost became a Catholic.

¶ ¶ ¶

The National Museum of Rome holds the world's largest collection of ancient Roman sculpture.

¶ ¶ ¶

I have a serious recommendation for anyone booking a cruise that will begin in Rome and not travel north to Milan, Florence, or Venice. If you need or expect or wish to buy any clothing―a nice dress, high-quality T-shirt, men's flat cap, cashmere sweater, anything―or shoes or accessories on your trip, buy them in Rome. If you don't, you'll regret it.

Rome has shops everywhere. You will find something you want to buy, I guarantee it. On the other hand, if you leave Rome thinking you will find an article of clothing in one city or another that won't make you look like you're blind or that you don't own a mirror, pray you come to your senses, find the ship's captain, and tell him to turn the ship around, you need one more day in Rome. It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than it is to find a decent shop of any kind in Naples.

|

| Typical street scene in Rome |

| Another typical street scene: not a motorcycle

sales lot but commuter parking |

|

|

|

| Via del Corso |

Via del Corso is the Rodeo Drive, 5th Avenue, and Champs-Élysees of Rome. You will find every high-end brand here with its own bricks-and-mortar shop: Prada, Gucci, Rolex, Louis Vuitton, Tag Huer, Hermès, Breitling, Zara, Dolce & Gabana, Bulgari, Fendi, Dior, Chanel, United Colors of Benneton, Jimmy Choo, Mont Blanc, Tiffany, etc., etc., etc. Other known brands with shops on Via del Corso or adjacent streets: Nike, Sephora, New Balance, Gap, Skechers, The North Face, and Calvin Klein.

And for the record, on any given street we walked in Rome, I saw more fountain pen shops than there are in all 23,000 square miles of northern California.

| | Here we are at Trevi Fountain |

|

|

It was winter and off-season, and yet every attraction was crowded in Rome. The outside of the Colosseum was so crowded we couldn't get close enough to get a decent photo without walking down a steep ramp that would've required an equally steep and ultimately unacceptable return trip uphill. Here's the best photo we could get from a far distance.

¶ ¶ ¶

The only pizza I ate away from the ship was in Rome and I didn't like it. It was a four-cheese pizza at Tempio di Bacco, and at least one of the cheeses tasted a lot like backyard dirt. Nevertheless, I did eat it all.

I have three levels of edibility. First, food I like and so I eat it. Second, food I don't like but I eat it anyway because someone else cooked it and I can see/smell that I can eat it without vomiting. Third, food I can't eat. The Roman pizza was a category 2.

|

One day I had this for lunch and dinner. |

Viking

|

| Viking Star |

We've watched TV commercials for Viking since 2013, ever since we began watching British detective shows on PBS Masterpiece Mystery. I decided back then that if we ever became old enough to go on a cruise, it would have to be a Viking cruise.

We were so well taken care of by everyone who worked on the ship, I have no interest in checking out any other cruise lines.

As I recall it, I had almost nothing to do with planning this trip. I steered clear of arranging the details like choosing which excursions to undertake at which stops. I didn't want to get emotionally invested, in case something caused us to cancel or postpone again.

As Mecca remembers it, I was involved in every decision on every detail.

I did initially co-decide to undertake a Mediterranean voyage and to travel with Viking. Many cruise lines go to the Mediterranean. But there's only one Viking.

|

| Sunrise on the way to Naples |

The best thing about Naples was the sunrise on the way there.

|

| Port of Naples |

|

Castel Nuovo, a medieval castle, now home

to the Neapolitan Society of Homeland History |

This might explain my disappointment with Naples. We walked into the city from the ship. I had researched fountain pen shops that were located there and the closest one to the ship was The Beauty of Paperwork, 1 mile away. I had an address and I had Google Maps on my phone. And when we arrived in the vicinity of the address, we couldn't find the pen shop, couldn't find the address on any storefront. We looked and looked and looked again. We went into hundred-year-old buildings, up old-fashioned elevators that looked like cages where I had to open and close the elevator doors by hand. One side of the street and then the other. The Google Maps marker seemed at one point to indicate the pen shop was inside a produce market. It was a wild goose chase. We spent 3 hours on it. We never found the store.

Sicily

|

The road we climbed to get

to the rustic village of Savoca |

On the island of Sicily, high in the hills above Messina, there is a small, remote village named Savoca. Somehow, sort of in the way Stanley discovered Livingstone, I presume, Francis Ford Coppola discovered the village of Savoca and planted Hollywood's flag there. He used Savoca to film all the Sicily scenes in The Godfather.

Bar Vitelli is where Michael Corleone asks Appolonia's father for her hand in marriage. It is also the place where I ate the best gelato I had on the trip.

| The church where Michael

and Appolonia get married |

|

|

Malta |

| Triton Fountain |

We had no expectations of Malta. We didn't have any idea what we would find in Valletta, the capital.

|

| View of Valletta Waterfront from the ship |

|

| Nighttime view |

Every port we stopped at in the Mediterranean was heavily defended with fortifications, mostly still intact, that have been there for 2,000-8,000 years.

Malta was celebrating Carnival while we were there.

|

| Typical street scene in Malta |

|

| Selfie |

|

View of the Mediterranean from behind

the Malta National Aquarium.

The photo is not processed.

The water really is that blue.

|

|

| The reading material I brought from home |

Corfu

|

| Port of Corfu |

|

| View of the Ionian Sea from the west end of Corfu |

|

Fellow devotees of

afternoon cappuccino |

Mecca's Fall

We had taken a tour bus from the ship on the east coast of Corfu to Paleokatristsa Monestery on the west coast. After that, the tour guide took us on a walk through modern Corfu. At the end of the walking tour we were invited to walk around on our own and take a shuttle bus back to the ship. So we walked around on our own and took a shuttle bus back to the ship.

When we arrived at the shuttle bus we boarded through the front door. The center aisle was dark because the sun was behind clouds and darker still toward the rear of the bus because the side-rear door was not open to let in what little ambient light there was. As we made our way toward the rear, passing the steps of the rear-side door, Mecca inadvertently put her left foot on the edge of the top step that she couldn't quite see and she fell down into the black hole that comprised the dark steps and the closed door. She was down there in pain and absolutely stuck because she had no way to get her feet under her and so no way to extricate herself. I wanted to call MacGyver but he was fictional. Eventually it was decided to open the door she was leaning against and have a handful of strongbacks catch her when she fell out. That was how it was done.

Unfortunately, for the rest of the trip she was in constant pain, and every day the pain was worse than the day before. Fortunately, she broke no bones, didn't tear any muscles or tendons or ligaments, didn't suffer a concussion.

Olympia

We are about to enter sacred real estate, equal to the Acropolis and the Parthenon. This is where the spiritual journey began for me on this trip. This is ancient Olympia, or rather what's left of it, which is mostly rubble.

| Seating area for the Olympians during

the opening ceremonies |

|

|

Olympic pageantry and ceremony are traditions that go back nearly 3,000 years. As the athletes walked to the stadium they paraded through a colonnade and paid tribute to Nike as they passed her statue on their left. Nike is the Greek goddess of victory.

|

| The statue of Nike stood atop that column |

After walking through the colonnade, the athletes, coaches, and judges would enter the Olympic stadium through this arch.

|

| The Olympic Stadium |

The ancient Greeks conducted their Olympics nearly 300 times―right here, every 4 years without fail, from 776 B.C.E to 393 C.E.

Kálamata

We visited two castles in Kálamata, Greece. The first was Pylos Castle.

|

The pink object in the lower right quadrant

is Mecca, waiting for me to leave the upper

level. The combined effect of her multiple

sclerosis and that fall on the bus made

the steep steps here impossible to attempt. |

The second castle was Methini Castle. Mecca went to this one. I didn't. I stayed in town and hung out with the cats.

Free-Roaming Cats and Dogs

We encountered free-roaming cats and dogs everywhere we went in the Mediterranean. They might technically be feral. But I've interacted with feral cats. And the interaction goes like this: I look at them, they run away.

.jpg)

These animals are not just friendly but openly friendly. I was at one site, sitting on a pile of flat rocks as if on a chair, and I felt this push from behind on my upper back near my left shoulder. I thought, aw, that feels just like a cat rubbing its whiskers against me, and instantly I wished it really were a cat. It was.

Crete

The Hammurabi Code is the oldest codified law in the world. Roughly 3,500 years ago, King Hammurabi of Babylonia received the law from, or so the story goes, the Babylonian god of justice Shamesh.

The Minoans lived on the island of Crete 3,000-3,500 years ago. They were the first civilization in Europe and were social and political ancestors of the Greeks.

|

The Minoans obtained a copy of the Hammurabi Code in Akkadian,

translated and transliterated it into Greek, and

finally carved the code into these stone tablets.

|

The carved Hammurabi Code on these stone blocks constituted the first codified law in Europe.

|

Seating for town hall meetings |

Rhodes

Every Mediterranean city and country we visited had fortifications that have survived since ancient times. But Rhodes went berserk.

|

This is a closeup of our view from the ship

|

|

This car rental agency occupies

a portion of the battlement |

|

The walk into the city was lined with these

battlements. The obelisk on the right in the

far distance is at the edge of the city. |

|

Zoom in to see the fortifications on

the other side of the inlet. |

The City of Rhodes is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. But one feature towers above the others.

The Colossus of Rhodes was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. It was a giant bronze statue with legs and feet that bestrode the entrance to the harbor. Now, two deer, each one perched on a column, indicate the location of where the feet and legs of the Colossus used to be.

| The closest deer is a doe.

The farthest is a stag,

marked with an arrow

in the photo below. |

|

|

While we walked around Rhodes we spotted a restaurant and decided to go get cappuccino. I also looked at the breakfast menu and saw something that reminded me of a mind-boggling phenomenon: Europeans are nuts about Nutella. On the menu was a Belgian waffle covered with Nutella and topped with a scoop of vanilla ice cream.

Ephesus, Turkey

This was one of the places St. Paul visited late in his life. Sometime afterward, he wrote a letter, an "epistle," to the inhabitants. You can find it in the Holy Bible. It's the book of Ephesians.

In the time of St. Paul, Ephesus was a Greek outpost. Over a thousand years later, the Ottoman Empire had other ideas. Modern Turkey has not offered to give it back.

The earliest inhabitants arrived there about 8,000 years ago.

In 2015, Ephesus was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

|

The Gates of Augustus

|

|

The Temple of Hadrian

|

|

The Library of Celsius, one of the largest

libraries in the ancient world. |

|

Stadium seating at the Theatre of Ephesus

|

|

Mosaic tile floor

|

|

Public toilet with room for

8 people in this row and

4 more around the corner |

|

The imprisonment of St Paul on Ephesus

occured in a structure, now gone, at

the top of this hill. |

Corinth

Yes, yes, yes. Corinth was where the Corinthians lived.

Apart from being a place St. Paul visited and wrote an "epistle" to, Corinth is known for the Corinth Canal. Ancient Romans conceived the canal during the Empire. They planned to cut it through the Isthmus of Corinth, which separates the Peloponnese from mainland Greece.

The ancients only partially built their canal. The Emperor Nero used 6,000 prisoners of various Roman wars as laborers. But they only made progress one-tenth of the way across the isthmus. Today, no remnants of the original canal remain.

Between then and the 19th century there had been several plans to finish the job or rebuild a canal from scratch. For a variety of reasons, these attempts never got further than the idea stage. Finally it was built between 1882 C.E. to 1891 C.E..

Denouement

Departure day was the day after Corinth. We disembarked from the Viking Star at 4:00 AM Central European Time for the bus ride to Athens International Airport. Our plane took off for Zurich at 6:35 AM. We took off from Zurich at 12:25PM Central European Time. From Zurich to LAX was a 10-hour flight. That's 10 hours in real time. LAX to Sacramento allowed a brief nap. We arrived home at bedtime.

Mecca is almost fully recovered from her fall inside the tour bus.

.jpg)

.jpg)